Very quickly (in 1859) the British Crown took direct control of the colony. But it wasn’t until WW1 began that Mahatma Gandhi returned to India, after 21 years in South Africa fighting for the rights of Indian immigrants. Gandhi was loyal to the British Empire and supported Britain in WW1. And on his return to India, he spent the first few years leading non-violent struggles on local grievances. Most Indians supported the British in their war effort against the Axis Powers; indeed 1.3 million Indian soldiers fought for Britain in WW1, and tragically 60,000 of them died.

But the British knew that not all Indians were willing to support colonial control of India. In 1915, some of the most radical Indian nationalists planned the Ghadar Mutiny, which called for soldiers in the British Indian Army to revolt in the midst of the Great War. The Ghadar Mutiny never happened because the plotters were infiltrated by British agents. Yet the events increased even further distrust among British officers toward the people of India.

The unrest seemed of greatest concern to the British in the Punjab which had been a vital economic & military asset, trade heart of the world empire. The colonial army recruited heavily in the region and in WWI, soldiers from Punjab constituted more than half of the British Indian Army.

Almost immediately the colonial government used WW1 as the time to introduce the diabolical Defence of India Act of 1915. This wartime legislation gave the government endless powers of preventive detention, to lock up Indians without trial and to restrict speech, writing and movement.

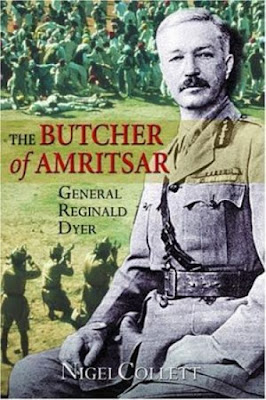

Book by Nigel Collett

Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer in the foreground

Soldiers mowing down civilians in the background

In March 1919, the British extended its wartime emergency powers into peacetime via the Anarchical & Revolutionary Crimes Act/Rowlatt Act. For example the Act authorised the government to arrest Indians without a warrant and to imprison suspected revolutionaries for two years without a trial. It also placed strict controls on the press.

Not surprisingly, in the immediate aftermath of the war and the Rowlatt Act, pressure for Indian independence mounted. Gandhi immediately expressed his opposition to the Rowlatt Act and called for a nationwide general strike on 6th April 1919. He asked people to engage in peaceful resistance, observe a daylong fast and hold meetings to demand the repeal of the legislation.

But anger in the northern Indian province of Punjab was already heating up before Gandhi called for civil resistance. Across the state, Hindu, Muslim and Sikh nationalists had been agitating against the Rowlatt Act; Gandhi’s call raised the popular fervour against the law to a boil.

When news of the arrest of Indian nationalist leaders in the Sikh holy city of Amritsar emerged, Gandhi decided to travel to Punjab. The colonial government stopped Gandhi’s train, arrested him and sent him back to Bombay. Protesters in Amritsar went on a rampage, clashed with the authorities, looting banks and public buildings.

Within a month, violent street scuffles broke out between Europeans and Indians in the streets of Amritsar. The local military commander, Brigadier-Gen Reginald Dyer, took over from the civil authorities and banned all public meetings (four+ people) which could be dispersed by force. He issued orders that Indian men could be publicly lashed for approaching British police officers.

On the very day that free assembly was retracted, 15,000-20,000 Indians celebrating Sikh New Year at Jallianwala Bagh walled gardens. General Dyer, certain that the Indians were beginning an insurrection, led his armed soldiers via the narrow entrances to the public garden. Thankfully the two armoured cars with mounted machine guns were too wide to fit through the passage-ways into the gardens.

Without warning, Gen Dyer ordered his soldiers to open fire and to aim for the most crowded parts of the gathering. People screamed and ran for the exits, trampling one another in their terror, only to find each way blocked by soldiers. Dozens jumped into a deep garden well to escape the gunfire and drowned. The shooting continued until the troops ran out of ammunition. And only then did Dyer order a ceasefire and withdrew his men, leaving the dying and wounded where they lay. The authorities imposed a curfew, preventing families from saving the wounded who were in piles where they lay, or finding their dead. By morning the final death toll was almost 1,000 Indian men and boys.

The colonial government tried to block the massacre story from spreading across India and abroad. But within India, ordinary people quickly became politicised, and nationalists lost all hope that the British government would deal with them in good faith. India's recent massive contribution to WW1 had meant nothing, apparently.

Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar

Deep Memorial Well where dozens jumped in 1919, to escape the gunfire and drowned.

Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar

Memorial Wall still riddled with 1919 bullets

Speaking in the British House of Commons, Winston Churchill called the massacre monstrous. But many British senior political and army figures hailed General Dyer’s actions as necessary to keep an unruly and potentially seditious population in order. So Lord Hunter, a Scottish judge, chaired a Committee of Inquiry into the Amritsar massacre and its outcome. General Dyer testified that he surrounded the protestors and did NOT give any warning before giving the order to fire; he did not seek to disperse the crowd, but to punish the people of India generally. He would have used the machine guns to kill many more people, had he been able to get them into the garden!

Gen Dyer’s defence was brutal, even though he continued to believe that he was the Saviour of India until he died. But the Committee of Inquiry’s conclusions were rightly damning; Dyer was strongly censured and forced to resign from the Indian Army. Unfortunately he was never prosecuted for the mass murders of civilians.

Yet many, particularly the colonial bureaucracy, thought that Dyer had acted solely to prevent another Indian Mutiny. Sir Michael O'Dwyer, Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab from 1912-19, warmly supported Colonel Dyer's actions in Amritsar. Whether Governor O'Dwyer actually planned Dyer’s massacre in advance or not, Sir Michael O’Dwyer was assassinated in London in 1940 by a Sikh revolutionary.

Dyer died in England in 1927. But the massacre continued to sour relations between British and Indian politicians for years. Read Origins, who saw the massacre as the beginning of the end of British rule in India. Read Gyan Prakash who called it the massacre that led to the end of the British Empire.

.jpg)

.jpg)

8 comments:

Origins is a great reference, thank you. The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain was very interesting.

Hel

Brig General Dyer was a disgrace to Britain and the Empire. No wonder the Indians felt betrayed.

Hello Hels, Massacres of defenseless people are rarely justifiable and do not go down well in history, no matter what side the aggressors are on. It seems logical that those in authority would take a moment to reflect on the probable repercussions of a massacre, and whether that is what they really want to initiate, before proceeding recklessly.

--Jim

p.s. I was speaking historically. Today the new rule is to ruthlessly attack a people in order to spark more hatred for them in a "base of followers."

Student

when we looked at the British Raj in lectures, I didn't know about Origins or similar references. My only certainty back then was that while students would not read someone's PhD thesis of 100,000 words, they were very likely to read a history blog post of 1,500 words :)

Joseph

Brig General Dyer would have been a disgrace in any colonised country, but how much worse in India. Firstly India was The Jewel Of the Crown of the vast British Empire and Queen Victoria was the Empress of her beloved India.

Secondly over one million Indian troops served overseas in World War 1, of whom 75,000 died and another 67,000 were wounded. It was one of the greatest contribution to Britain and the Allies in the war that finished _just_ before the Amritsar Massacre.

Parnassus

I agree. Massacres of unarmed civilians in a locked-in city square are genocide. But what if the obscene laws that were enacted before the massacre, and the arming of the troops before the massacre, were carefully pre-planned. It would be of little moral value for General Dyer to say he was "just following orders from the Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab".

Really helpful post for them those are looking for steps of arts and architects. This will be helpful for beginners, Keep giving updates.

Residential Architects Birmingham Michigan

steffanronan

Many thanks. When I first started this blog back in 2008, there was indeed a concentration on architecture and the various visual arts. But I hope you still enjoy the history posts, like this one, even when there is very little architecture still intact.

Post a Comment