Up until 1304 the diamond was held by the Indian Rajas of Malwa. By 1304 the diamond came into the possession of the Emperor of Delhi, Allaudin Khilji. Then in 1339 the diamond was taken to the city of Samarkand (now in Uzbekistan), where it stayed for centuries.

Clearly the diamond variously belonged to all the Indian and Persian rulers who fought bitter battles throughout history. In 1526 the Mogul ruler Babur mentioned the diamond, gifted to him by the Sultan Ibrahim Lodi of Delhi, in his writings. At 793 carats, it must have looked superb.

Shah Jahan (1592–1666) was the ruler who commissioned the Taj Mahal mausoleum. But he also commissioned the very glamorous Peacock Throne, the Mughal throne of India in Delhi. The Koh-I-Noor was mounted on this very special piece of furniture. When he was imprisoned by his son Aurangazeb, Shah Jahan could only ever see his beloved Taj Mahal via the reflection in the diamond.

Aurangzeb might have been cruel to his own father, but at least he protected the diamond by having it cut down by a Venetian specialist to 186 carats, then brought the Koh-I-Noor to the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore. Aurangzeb passed the jewel on to his heirs but Mahamad, Aurangzeb’s grandson, was not a great ruler like his grandfather. Sultan Mahamad lost a decisive battle to Nader.

Queen Alexandra's corontation 1902,

with the Koh-i-Noor in the centre of her crown

Emperor Nader Shah, Shah of Persia (1736–47) and the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Persia, invaded the Mughal Empire, eventually attacking Delhi in March 1739. So Nader Shah took the diamond back to Persia and gave it its current name, Koh-i-noor/Mountain of Light. But Nader Shah did not live for long, because in 1747 he was assassinated and the diamond went to his general, Ahmad Shah Durrani.

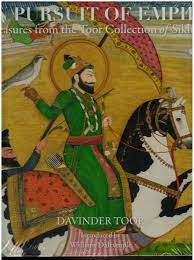

The defeated ruler of Afghanistan Shah Shuja Durrani brought the Koh-i-noor back to the Punjab in India in 1813 and gave it to Ranjit Singh, founder of the Sikh Empire. Durrani made a deal: he would surrender the diamond to the Sikhs in exchange for help in winning back his Afghan throne.

Most of the Punjab region (including Delhi and Lahore) was annexed by Britain’s East India Company in 1849, and then moved to British control. The last Maharajah of the Sikhs, the 10 year old child Duleep Singh, wept when land and treasures of the Sikh Empire were confiscated by governor-general of India, Lord Dalhousie, and taken as war compensation. The diamond, the most tragic theft of all, was formally transferred to the treasury of the British East India Co in Lahore! Even the Treaty of Lahore specifically discussed the fate of the Koh-i-Noor, in writing.

The diamond was proudly shipped by Lord Dalhousie to Queen Victoria in July 1850. It was a symbol of Victorian Britain's imperial domination of the world and its ability to take the most desirable objects from across the Empire... to display in British triumph.

And then it was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Crystal Palace, in the southern central gallery. World Fairs were often used to display a country’s greatest treasures. So, as expected, there was enormous excitement in Crystal Palace when official commentators and the general public first saw the jewel. Although there were 100,000 other exhibits displayed in Crystal Palace, the queues to see Queen Victoria’s diamond were the longest of all.

In 1852 the Queen decided to reshape the diamond and it was taken to a Dutch jeweller to re-cut it. The Koh-i-Noor had originally been one of the world’s largest uncut diamonds, but by 1852 the size had been reduced again, this time down to 106 carats. Queen Victoria wore the diamond occasionally afterwards. She wrote in her will that the Koh-i-noor should only be worn by queens.

After Queen Victoria died, the Koh-i-Noor diamond was crafted into the Crown Jewels and displayed at the Tower of London.

The Koh i Noor diamond, set in the Maltese Cross at the front of the crown

106 carats during Victoria's reign.

In 1947, the partition of India led to the Punjab being divided into the newly created Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. This partition has influenced the cases brought in British courts over the last few years. Recently the descendants of the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire said they were forced to hand over the Koh-i-Noor diamond to the British; they launched a court action in the UK to get the diamond back in Sept 2012. The case depended on the diamond being one of the many artefacts taken from India under ugly circumstances. The Indian lawyers claimed the British colonisation of India had stolen wealth and destroyed the country’s psyche. Their court case failed.

But India was not the only nation with a historical claim to the diamond – it had passed through Persian, Hindu, Mughal, Turkic, Afghan and Sikh owners centuries before it was seized by the British in the C19th. So expect the British to face another legal battle, after a Pakistani judge accepted a petition demanding that the Queen hand the $200 million stone back to them. Mind you, in 2013 the Prime Minister David Cameron said that returning the stone was out of the question. Will the next prime minister say the same to Persia/Iran?

Historians last question is "what is the proper response to imperial looting?" Read the brand new book Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand, published by Bloomsbury in 2017. The history of the Koh-i-Noor, that was accepted by the British, is no longer a glorious piece of the nation’s colonial past. That history is finally challenged! The resulting version, now published, is one of greed, murder, wars, torture, colonialism and appropriation.

In 1947, the partition of India led to the Punjab being divided into the newly created Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. This partition has influenced the cases brought in British courts over the last few years. Recently the descendants of the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire said they were forced to hand over the Koh-i-Noor diamond to the British; they launched a court action in the UK to get the diamond back in Sept 2012. The case depended on the diamond being one of the many artefacts taken from India under ugly circumstances. The Indian lawyers claimed the British colonisation of India had stolen wealth and destroyed the country’s psyche. Their court case failed.

But India was not the only nation with a historical claim to the diamond – it had passed through Persian, Hindu, Mughal, Turkic, Afghan and Sikh owners centuries before it was seized by the British in the C19th. So expect the British to face another legal battle, after a Pakistani judge accepted a petition demanding that the Queen hand the $200 million stone back to them. Mind you, in 2013 the Prime Minister David Cameron said that returning the stone was out of the question. Will the next prime minister say the same to Persia/Iran?

Historians last question is "what is the proper response to imperial looting?" Read the brand new book Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand, published by Bloomsbury in 2017. The history of the Koh-i-Noor, that was accepted by the British, is no longer a glorious piece of the nation’s colonial past. That history is finally challenged! The resulting version, now published, is one of greed, murder, wars, torture, colonialism and appropriation.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)