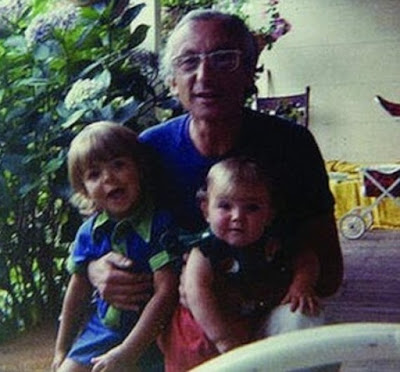

Leonard Warwick and his daughter on a hunting trip, c1982

Guns in Australia were not illegal back then, but they were not a good look.

In a progressive programme of the Whitlam Federal Government, the Australian Family Court started in Jan 1976. But despite the high idealism of the court's creators, they failed to realise one truth: that in a marital battle, one side would be more embittered than the other. Between 1980-85 in Sydney, four people were killed, dozens critically injured and maimed in a cruel reign of terror that targeted the Family Court judges and their families. And there were strong links between a particular suspect and the deaths.

Despite the horror of these shootings and bombings in Sydney from 1980-5, and a prime suspect publicly named by the Coroner, the police investigations failed to make an arrest.

Despite the horror of these shootings and bombings in Sydney from 1980-5, and a prime suspect publicly named by the Coroner, the police investigations failed to make an arrest.

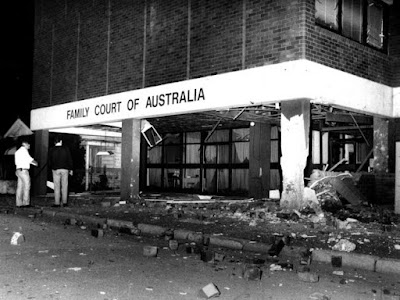

Family Law Court, Parramatta

bomb exploded in the outside foyer in 1984

What had happened? Married in 1974, Leonard Warwick and his wife Andrea Blanchard had a daughter. But by 1980 they were often before the Family Court, fighting for custody of this young girl. Leonard wanted full time custody for himself whereas Andrea agreed to share it.

The wife fled to her family home and her brother Stephen Blanchard helped her recover her daughter from the husband. Thus Stephen became a target of her husband's anger. In Feb 1980 Stephen Blanchard was murdered in his family home. Six days later his body was found on the Hawkesbury, across Sydney.

Later that month, Family Court Judge David Opas (1936–80) reduced Warwick's access to his daughter. The Coroner's Court heard evidence he had told his wife that “Judge Opas wouldn't be there much longer”. 5 weeks later the judge was shot dead at his Woollahra front door! It was a tragedy.

Judge David Opas with his two beloved children

Judge Richard Gee's home in Belrose, Sydney

Later that month, Family Court Judge David Opas (1936–80) reduced Warwick's access to his daughter. The Coroner's Court heard evidence he had told his wife that “Judge Opas wouldn't be there much longer”. 5 weeks later the judge was shot dead at his Woollahra front door! It was a tragedy.

Front page of Daily Mirror Monday July 4, 1984

Judge David Opas killed by a mystery man

Judge David Opas killed by a mystery man

In July 1983 the judge who replaced Judge Opas in the custody case, Judge Richard Gee, made another order limiting the father's time with his daughter. Then in Mar 1984 a bomb exploded at the Gee home. The judge and his two children narrowly escaped death, but it destroyed the family’s sense of security.

In Apr another bomb exploded outside the front of the Parramatta Family Court where the family's cases had all been heard; fortunately no-one died. But three months later there was another explosion at the Greenwich home of the judge who had taken over from Judge Gee, Judge Ray Watson. His wife, Pearl Watson, was instantly killed by triggering a bomb at their front door. The then-prime minister Bob Hawke offered a $500,000 reward, still unclaimed.

NSW Kevin Waller's coronial inquiry heard Leonard Warwick was the prime suspect for all the attacks, but that the police had insufficient evidence to lay charges. Being a judge was in any case often isolating and unpopular, but THIS bloody terror campaign struck at the heart of the integrity of the justice system and intimidated judicial officers. And the fact that the murderer was still at large was even worse. The Family Court was a newish agency in no-fault divorce, but litigious fathers hated judges for “unfairly awarding custody to mothers in too many cases”.

In Apr another bomb exploded outside the front of the Parramatta Family Court where the family's cases had all been heard; fortunately no-one died. But three months later there was another explosion at the Greenwich home of the judge who had taken over from Judge Gee, Judge Ray Watson. His wife, Pearl Watson, was instantly killed by triggering a bomb at their front door. The then-prime minister Bob Hawke offered a $500,000 reward, still unclaimed.

NSW Kevin Waller's coronial inquiry heard Leonard Warwick was the prime suspect for all the attacks, but that the police had insufficient evidence to lay charges. Being a judge was in any case often isolating and unpopular, but THIS bloody terror campaign struck at the heart of the integrity of the justice system and intimidated judicial officers. And the fact that the murderer was still at large was even worse. The Family Court was a newish agency in no-fault divorce, but litigious fathers hated judges for “unfairly awarding custody to mothers in too many cases”.

the bomb exploded in March 1984

A coronial inquiry in 1986 heard evidence that the only common link in every one of the seven attacks was the former NSW fireman and skilled bushman Leonard Warwick who still lived in Sydney. His former wife Andrea Blanchard bravely spoke on tv about the coronial evidence re the prime suspect, her ex-husband.

A 2013 investigation by Seven Network's Sunday Night programme revealed new evidence and witnesses the police had failed to find. NSW coroner Kevin Waller called for the suspected Sydney killer to finally be tried.

What she found shocked police. The core of Warwick’s abuse was Andrea, whom he violently assaulted and harassed. So the ex-wife was running a major risk; revealing the murders was a dangerous sacrifice that no domestic abuse victim should ever have to pay. After Marshall’s story aired, NSW Police formed a taskforce to re-examine the cases.

In July 2020 73-year-old Leonard Warwick was found guilty in the NSW supreme court of 20 crimes i.e 6 Sydney attacks between Feb 1980-July 1985. In Sep 2020 he was given a full life sentence.

Photo credits: Daily Mail

There were break-ins at the Jehovah's Witness Kingdom Hall in Casula SW Sydney in July 1985. Nothing was stolen but the following Sunday a massive explosion splintered the hall as the 150+ churchgoers were in prayer. One man was killed by the bomb at the congregation where Andrea Warwick's sister, Judy, was a devoted member.

The original police investigation was thorough. Yet the judges and magistrates should have had the right to feel confident that their decisions would be respected; that anyone who challenged the law with violence would be pursued and prosecuted. Families and victims of this notorious unsolved crime spree also asked why a 3-decade police investigation failed to bring a serial killer to justice.

The original police investigation was thorough. Yet the judges and magistrates should have had the right to feel confident that their decisions would be respected; that anyone who challenged the law with violence would be pursued and prosecuted. Families and victims of this notorious unsolved crime spree also asked why a 3-decade police investigation failed to bring a serial killer to justice.

A coronial inquiry in 1986 heard evidence that the only common link in every one of the seven attacks was the former NSW fireman and skilled bushman Leonard Warwick who still lived in Sydney. His former wife Andrea Blanchard bravely spoke on tv about the coronial evidence re the prime suspect, her ex-husband.

A 2013 investigation by Seven Network's Sunday Night programme revealed new evidence and witnesses the police had failed to find. NSW coroner Kevin Waller called for the suspected Sydney killer to finally be tried.

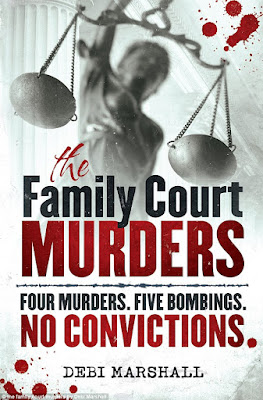

Debi Marshall's book

The Family Court Murders, 2014

I didn’t read The Family Court Murders (2014) by true-crime writer and investigative journalist Debi Marshall because her deep analysis of the case became an important ABC-TV series May 2022, the definitive story of the Family Court Murders where the team investigated this cold case. Decades after 1985, witnesses were still frightened to speak; family members still lived in dark grief and fear; and widows and orphans had no closure. It was still a dangerous investigation into the prime suspect.

What she found shocked police. The core of Warwick’s abuse was Andrea, whom he violently assaulted and harassed. So the ex-wife was running a major risk; revealing the murders was a dangerous sacrifice that no domestic abuse victim should ever have to pay. After Marshall’s story aired, NSW Police formed a taskforce to re-examine the cases.

In July 2020 73-year-old Leonard Warwick was found guilty in the NSW supreme court of 20 crimes i.e 6 Sydney attacks between Feb 1980-July 1985. In Sep 2020 he was given a full life sentence.

Photo credits: Daily Mail

.jpg)

18 comments:

When Debi Marshall did the research about the Family Court Murders she admitted straight away that some very crucial pieces were still missing from the long, miserable story. But the sad truth is that the original witnesses of the 1980s events have either died years ago or have forgotten the details over the decades.

Weren't the judges and staff in the Family Court protected against angry litigants?

Ex Pat

the longer the delay, the less chance for reliable information *nod*. Of course there was no DNA testing in the early 1980s, nor were there evidential photos or videos taken on mobile phones. But it seems to me that reliable witnesses didn't give contemporary evidence because they were afraid for their lives. I would have been too.

Silken

good question! The judges KNEW they would be targets because the Family Court was not dealing with a well behaved section of society. So why, when this Federal Dept was established, were no security measures allocated to the Family Law Courts? Lack of resources? A trust in fathers' good will? A failure to address anti-judge violence in public places?

I must find out what protection is given to Family Court staff and clients now.

From my blog today where I spoke of an unsolved case in the UK it shows that these examples of missed or ignored evidence are all too common. The one here was also re-opened and has now been solved. It could have been achieved almost 30 years ago but poor detective work and evidence not handed over to the court led to the case being unsolved and the murderer being always a free person. He has now been locked up.

Maybe there are matters we are not aware of but it simply sounds like very poor police work to me. Yes, there were not the technological resources available back then, but connecting up a few dots should not be so difficult.

You can't help but think something should have happened much earlier. Circumstantial evidence should have been given more weight.

Rachel

Rikki Neave's case took a very long time to be properly tried and the murderer locked away. Not the first time a murderer has got away with the crime for the rest of his life, or for very long time after the initial tragedy :( However poor detective work from experienced officers and evidence not handed over to the court sounds dodgy but perhaps not corrupt.

In the Sydney case in 1980, the Coroner's Court heard evidence about Warwick telling his wife that "Judge Opas wouldn't be there much longer". Even when the prime suspect was publicly named by the Coroner, the police still failed to make an arrest. More than dodgy, I would say now.

Andrew

Not difficult at all. Linking the dots meant finding that

1. Stephen Blanchard was Warwick's brother in law.

2. and 3.The first judge and the second judge's wife were both strongly involved in Warwick's case, to the father's detriment, so they were killed.

4. The man killed in Jehovah's Witness Kingdom Hall was in Warwick's ex-sister in law's church

These four deaths may not have been legal proof by themselves, but they were very persuasive.

Fun60

I checked your suggestion and offer the following.

Circumstantial evidence does not directly prove a fact. It occurs when evidence of a related fact is provided from which the jury can infer the existence of the fact in issue. This will be used, for example, when no one has directly witnessed the facts which the prosecution must prove. There is nothing in the law (in Victoria at least) that makes proof by circumstantial evidence unacceptable by itself.

To find the accused guilty, guilt must not only be a reasonable inference, it must be the ONLY reasonable inference which can be drawn from the circumstances established by the evidence. So you are quite right.

Hi Hels - such a sad story ... but thanks for sharing it with us - people can be cruel, others can be stupid ... not fun but I'm glad he is spending time in gaol now. All the best - Hilary

Hilary

I started writing the post with a very clear view of right, wrong, negligence and incompetence. But the shooting and bombing campaign in Sydney continued from 1980-5, and wasn't resolved in the NSW supreme court until 2020. So while I understand that perhaps the family murders were too hard to pursue, the murders of judges and their families were beyond belief. Killing judges is the equivalent of killing prime ministers, archbishops, governors general or university chancellors.

I watched this DOCCO . Very good and makes you think that police with dodgy powers of persuasion might not be such a bad thing after all ........Only kidding . Its awful that people had to die and live in terror due to lack of evidence when everything pointed to this appalling thug .His Ex was SOOOOO brave

mem

me too. I remember the murder of Judge David Opas very well, probably because my parents knew Judge Philip Opas in Melbourne. Philip defended Ronald Ryan who was found guilty in 1965 and hanged two years later because of a loathsome Premier Bolte :(

I still find the standards of certainty required, before a criminal is charged, to be scarily unreliable.

Boa tarde. Desejo uma excelente quinta-feira com muita paz e saúde.

Luiz

thank you. This is an important topic for most of us.

Except the Watsons unit being bombed happened BEFORE 1984, my mother in law was an acquaintance of Pearls (she lived in St Lawrence St and Pearl lived in Greenwich Rd,

I lived in the next suburb over, and remember the day the bomb went off, I heard it and felt it, I don't know what's going on here but this is weird, why change the year of the bombing?

Anonymous said...

Except the Watsons unit being bombed happened BEFORE 1984, my mother in law was an acquaintance of Pearls (she lived in St Lawrence St and Pearl lived in Greenwich Rd, I lived in the next suburb over, and remember the day the bomb went off, I heard it and felt it, I don't know what's going on here but this is weird, why change the year of the bombing?

September 11, 2024 6:34 am

Hels says:

Do you have a more reliable reference, anon? I was citing Australasian Legal Information Institute:

https://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/AUJlLawSoc/1992/8.pdf

Post a Comment