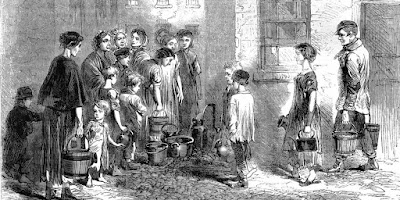

In the mid 1800s, the good citizens of London didn’t have deep sewage toilets inside their homes. Citizens in the world’s biggest city used communal wells & pumps to get water needed for drinking, cooking and washing. Septic systems were so primitive that most buildings dumped untreated human and animal waste directly into the Thames River, or into open pits.

Cholera was an intestinal disease that caused death within hours of vomiting or diarrhoea appearing. The first British cholera cases were reported in 1831; from 1831-54, tens of thousands of people died of it.

London children bathed in, and drank from the same filthy streams used as slum sewers.

History Collection

Dr John Snow (1813–58), born into a working class family, believed that sewage-contaminated water caused cholera. Dr Snow published an article in 1849 outlining his theory, but doctors and scientists thought he was misguided; they stuck to their view that cholera was caused by stinking miasma. Dr Snow believed sewage dumped into the river or cesspools near town wells contaminated the water supply, and rapidly spread disease.

In Aug 1854 London’s Soho was hit by a terrible cholera outbreak, the third in London after 1832 and 1849. Dr Snow, who lived nearby, set out to prove his contaminated water theory. Where Cambridge St joined Broad St, there were 500+ cholera fatalities in 10 days. When he learned of the timing and extent of this outbreak, he zoomed in on the Broad St pump.

Dr John Snow (1813–58), born into a working class family, believed that sewage-contaminated water caused cholera. Dr Snow published an article in 1849 outlining his theory, but doctors and scientists thought he was misguided; they stuck to their view that cholera was caused by stinking miasma. Dr Snow believed sewage dumped into the river or cesspools near town wells contaminated the water supply, and rapidly spread disease.

In Aug 1854 London’s Soho was hit by a terrible cholera outbreak, the third in London after 1832 and 1849. Dr Snow, who lived nearby, set out to prove his contaminated water theory. Where Cambridge St joined Broad St, there were 500+ cholera fatalities in 10 days. When he learned of the timing and extent of this outbreak, he zoomed in on the Broad St pump.

Dr Snow tracked the data from hospital and public records, examining when the outbreak began and whether the victims drank Broad St pump water. Those who lived or worked near the pump were the most likely to use the pump and thus contract cholera. By using a geographical grid to chart deaths from the outbreak and investigating access to the pump water, Snow was recording proof that the pump was the epidemic source.

Snow also investigated groups of people who did NOT get cholera and asked whether they drank pump water or not. This would help him rule out other possible sources of the epidemic. A workhouse near Soho had 535 inmates but no cases of cholera, for example. This was because, he discovered, the workhouse had its own clean well!

And men who worked in a brewery on Broad St, making malt liquor, drank the liquor they made from the brewery’s own well. Not one of those men contracted cholera! Snow had proved that the cholera was not a problem in Soho EXCEPT among people who drank water from the Broad St pump.

In 1854, Dr Snow took his research results to the town officials and convinced them to remove the pump-handle, making it impossible to draw water. The officials were reluctant, but took the handle off as a trial, and found the cholera outbreak ended almost immediately. Eventually people who had left their homes and businesses in the Broad St area began to return.

John Snow and the Cholera Epidemic of 1854

by Charles River

Despite the success of Snow’s theory in curtailing Soho’s cholera epidemic, Board of Health reports downplayed Snow’s evidence as guesswork. Although Snow’s careful mapping became very important in locating cholera cases, public officials refused to clean up the drains and sewers.

cholera deaths in red, pumps in blue

For months after, Snow continued to track every case of cholera from the 1854 Soho outbreak and traced almost all of them back to the pump. But what he could NOT prove was where the contamination came from in the first place. Officials argued there was no way sewage from town pipes leaked into the pump and Snow couldn’t say whether it came from open sewers, drains under buildings, public pipes or cesspools.

Even a minister, Rev Henry Whitehead, challenged Dr Snow. Rev Whitehead was very troubled by the outbreak and its aftermath, but argued the outbreak was caused not by tainted water, but by God’s divine intervention. The Rev felt that many of the news reports were exaggerated and noted that even though the population of the area was decimated, there was no panic. Within a few weeks of the epidemic, Reverend Whitehead wrote his own account, entitled The Cholera in Berwick Street (1854). Not surprisingly, public officials took many more years before making improvements.

Dr Snow was not the last research-focused doctor who couldn’t convince the medical authorities of his discoveries. In the 1860s, Edinburgh surgeon Joseph Lister read a Louis Pasteur paper proving that fermentation was due to microorganisms. Lister was convinced that the same process accounted for wound sepsis, but surgeons wouldn’t use Lister’s antiseptic methods.

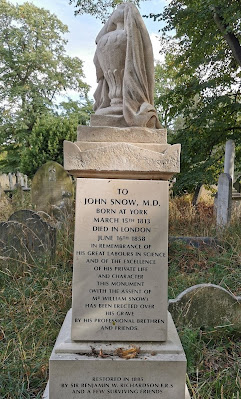

There is a memorial at the spot in Broadwick St (ex-Broad St) Soho where Snow proved cholera was spread through infected drinking water in 1854. See the water pump with its handle removed, opposite The John Snow Pub.

For months after, Snow continued to track every case of cholera from the 1854 Soho outbreak and traced almost all of them back to the pump. But what he could NOT prove was where the contamination came from in the first place. Officials argued there was no way sewage from town pipes leaked into the pump and Snow couldn’t say whether it came from open sewers, drains under buildings, public pipes or cesspools.

Even a minister, Rev Henry Whitehead, challenged Dr Snow. Rev Whitehead was very troubled by the outbreak and its aftermath, but argued the outbreak was caused not by tainted water, but by God’s divine intervention. The Rev felt that many of the news reports were exaggerated and noted that even though the population of the area was decimated, there was no panic. Within a few weeks of the epidemic, Reverend Whitehead wrote his own account, entitled The Cholera in Berwick Street (1854). Not surprisingly, public officials took many more years before making improvements.

Dr Snow was not the last research-focused doctor who couldn’t convince the medical authorities of his discoveries. In the 1860s, Edinburgh surgeon Joseph Lister read a Louis Pasteur paper proving that fermentation was due to microorganisms. Lister was convinced that the same process accounted for wound sepsis, but surgeons wouldn’t use Lister’s antiseptic methods.

Expand image to see John Snow Pub

In 1865 when cholera returned to London, Rev Whitehead focused back on cholera. Dr Snow had already died, leaving Whitehead as the main authority on the earlier Broad St outbreak. Because of rising public alarm, Rev Whitehead re-published his work, acknowledging that cholera was a water-borne disease. In 1866, cholera broke out in the East London slums and spread by contaminated water to thousands.

Thankfully German physician Dr Robert Koch pursued the cause of cholera further in 1883 when he isolated bacterium vibrio cholerae. Dr Koch determined that cholera was not contagious from person to person, but was spread ONLY through unsanitary water, a late victory for Snow’s theory. Note that the C19th cholera epidemics in Europe and U.S ended after cities finally improved water supply sanitation.

The World Health Organisation suggests 78% of Third World countries’ citizens are still without clean water supplies, making some cholera outbreaks an ongoing concern. Now scientists call Dr Snow the pioneer of epidemiology/public health research. Much modern research still uses theories like his to track the sources and causes of many diseases. And now that bombed-out Mariupol faces a cholera epidemic, we understand that outbreaks are definitely an ongoing concern.

Dr J Snow's cemetery stone

Guest blogger: Dr Joe

.jpg)

.jpg)

18 comments:

Thank you for this. It is an amazing story about Dr Snow and his findings. I know that in Norwich where I live the brewery workers (we had many large breweries in the city at that time) escaped the cholera epidemics because they drank beer and not water and the brewery families in the St Benedicts area of the city did not touch the water from the pumps because they had worked out for themselves that the water was not safe.

Rachel, of 535 people who worked in a London brewery during the epidemic, 99% survived because workers were allowed to drink as much of their malt liquor as they liked. I understand why brewery workers would prefer free beer to water anyhow, but would they have given the free beer to their wives and children?

Those Norwich brewery workers were cleverer than the London doctors. They made their own decisions and it turned out they were correct.

Hi Hels - the 18th century was an amazing time period for learning, recording, researching ... and philanthropy. My father's school in Rutland, about 50 years before he attended, moved itself lock, stock and barrel to Wales to escape typhoid in the town ... an enlightened headmaster organised this.

While London was exploding population-wise ... there was a huge amount of change - the Necropolis railway, new cemeteries on the outskirts of London (as they were then) Bazalgette's sewer - is still in operation today ... it's only recently been added to ... it is brick built - amazing workmanship - let alone help to cleaning up central London, before it was expanded. The embankment was built to convey the sewer ...

Dr John Snow was most definitely integral in being a part of improvements around London ... particularly this outbreak.

Fascinating ... thanks - Hilary

Hilary, correct. I should have mentioned Bazalgette's project in the post, but Snow had died and London was changing. Waterborne diseases like cholera killed so many Londoners in 1831-2, in 1848-9 and 1853-4 that legislation for the purification of the Thames meant the Metropolitan Board of Works got moving. Bazalgette planneded and built a system of intercepting sewers, pumping stations and treatment works that cleansed the Thames of sewage and helped to rid London of cholera.

I believe that they did. They also drank in the many hostelries in the city centre so it was not only the free beer.

I know why a stinking miasma could make people miserable, and wanting to leave London. But I don't understand why the medical authorities would believe a terrible smell could kill tens of thousands of people.

Student of History. Miasmic theory proposed that diseases were caused by the presence of poisonous emanations from putrefying carcasses or moulds. The foul smell didn’t cause the disease itself but doctors believed that the miasma entered the body and caused diseases like cholera & malaria.

Dr Snow concluded that cholera was caused by a germ cell, not by bad air. But Snow’s theory was not accepted in the 1850s since his germ theory rejected the miasmic theory. Dr William Farr was the dominant epidemiologist in the mid C19th and he too firmly rejected germ theory.

Rachel Nothing wrong with free beer, then and now!

But even more importantly, the statistics recorded from the brewery workers helped to prove Dr Snow's views.

Also there is a theory that beer saved the world! In modern times beer has played an important role in refrigeration, the discovery of germ theory and modern medicine.

However, in medieval times when water was too dirty to drink, possibly it's most important function was to support the population. Beer was safe to drink and men, women and children drank it morning to night; certainly in England.

That possibly is still the case in some parts!

CLICK HERE for Bazza’s meaningfully minatory Blog ‘To Discover Ice’

bazza it is not surprising that beer was preferred, especially for breakfast.

During the brewing process, the malted barley and water lost any existing bacteria, so beer was automatically healthier.

Also beer had some nutritional value, where water has none - important in energising labourers before work.

Finally although beer was relatively low in alcohol, it did provide some pleasure in otherwise grim lives.

But beer was too expensive for most families. Water was free.

I often walk past that memorial pump in Soho and wonder how many people who see it realise its significance. Thank you for the interesting post and comments it invited.

Fun60 I too often wonder how many people recognise the significance of 19th century crises these days. The Soho pump and pub should stop people in their tracks, to ask what had happened.

Do undergraduate medical students still study the symptoms of, and treatments for diseases that are rare now but once devastated communities eg polio, diphtheria, AIDS, Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease, ebola and cholera. Every epidemic can come back again.

Thanks, Dr Joe, for a fascinating story! Amazing to think he couldn’t even convince people who should have been willing to listen. But there was some great science going on in the 19th century!

Sue There have been many cases where doctors made mistakes in diagnoses and treatments, so the medical profession as a whole rightly tends to be conservative. The problem in London was not that Dr Snow was a young upstart, telling more experienced doctors how to handle the terrible death rate in the mid 1800s. After all, Snow could have made terrible mistakes himself.

The problem was that the medical authorities would not look at Dr Snow's solid epidemiological evidence. Not only was he an early designer of modern epidemiology, his careful maps and records in tracing the source of a cholera outbreak in Soho could have greatly reduced any further outbreaks.

Boa tarde minha querida amiga. Parabéns pelo seu trabalho maravilhoso e pesquisa. Eu não conhecia esse tema.

Luiz

you are not alone. But epidemics continue to spread around the world, perhaps even faster than in Dr Snow's time eg Monkey Pox and a new variant of Covid arrived in the world just this month!! We need to move in 2022 with more speed and urgency than Dr Snow and his colleagues faced.

In The Great Stink, Michael discovers how Britain's first Super Sewer cleaned up the capital and inspired a fresh water revolution that would change the lives of millions of Victorians.

Good coverage of both Snow and Bazalgette, many thanks. The images in The Great Stink were excellent.

Post a Comment