by Zeev Rechter, 1933. Dezeen

When Tel-Aviv became a city in 1921, Meir Dizengoff was elected mayor. In 1925 Dizengoff asked Geddes to submit a master plan for the city, the limits being the Yarkon River in the North and Ibn Gvirol St in the East. Geddes presented a great report in 1927, soon approved by the City Council. He brief was to create a European Garden City for 40,000 citizens, planning wide, main streets on a grid pattern, single plots for family homes, small public gardens in side streets and open access to beaches. He specified mixed residential-commercial use on the main roads.

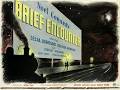

Cinema Theatre, now Cinema Hotel

1 Zamenhof St, 1934

Jerusalem Post

See the 1931 Master Plan of Tel-Aviv, drawn up by the Engineering Dept, on the original Geddes master plan of 1927. The primary roads, containing the city’s commercial activity, ARE broad and flow N-S. The secondary roads, residential, DO flow E-W. Wide tree-lined streets increased shade and colour, and provided a pleasant public space.

Inevitably Geddes’ plan had to be modified. The city’s density soon needed growth to cater to the flood of 1930s immigrants. By the height of British Mandate, the city was home to 150,00 people and 8,000 buildings! Of Geddes’ 60 public gardens, only half were ever built. The population today is c498,000!

The German Jews who arrived brought with them modernist architectural ideas from Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius. Just as Tel-Aviv was burgeoning on the Mediterranean (1933), many of the leading Bauhaus architects left Germany for Britain and USA, at least 20 Bauhausers and their colleagues migrated to the British Mandate in Israel.

By the mid-1930s it was the only city anywhere being built largely in the Bauhaus Style; its simple concrete curves, boxy shapes, small windows set in large walls, glass-brick verticals, asymmetrical facades, horizontal lines and balconies all washed in white. Tel-Aviv was a vision of startling white: c4,000 buildings, all built from 1933.

Inevitably Geddes’ plan had to be modified. The city’s density soon needed growth to cater to the flood of 1930s immigrants. By the height of British Mandate, the city was home to 150,00 people and 8,000 buildings! Of Geddes’ 60 public gardens, only half were ever built. The population today is c498,000!

The German Jews who arrived brought with them modernist architectural ideas from Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius. Just as Tel-Aviv was burgeoning on the Mediterranean (1933), many of the leading Bauhaus architects left Germany for Britain and USA, at least 20 Bauhausers and their colleagues migrated to the British Mandate in Israel.

By the mid-1930s it was the only city anywhere being built largely in the Bauhaus Style; its simple concrete curves, boxy shapes, small windows set in large walls, glass-brick verticals, asymmetrical facades, horizontal lines and balconies all washed in white. Tel-Aviv was a vision of startling white: c4,000 buildings, all built from 1933.

65 Shenkin St. 1935

Archinect

Tel-Aviv city council designers chose the Bauhaus style because of four ideological reasons:

1. Tel-Aviv architecture wasn't historically consistent with buildings from the past; there WAS no past.

2. The architects’ job was to improve society: housing for working families, trade unions, free clinics.

3. Prefabricated blocks of reinforced concrete, flat roof and sheer façade, no cornices or decoration saved money. Plus a three storey limit.

4. 20+ energetic Bauhaus-influenced architects fled Germany in 1933. Tel-Aviv city council drew on this amazing pool of available talent.

Bauhaus elements were characteristic of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, with some local Tel-Aviv adaptations. Glass was used sparingly, and narrow, horizontal windows appeared on many of Tel-Aviv’s Bauhaus buildings. Vertical windows were used on stairwells.

Along the Mediterranean, balconies increased the movement of breezes and sea views. So overhanging brows blocked direct rays of sunshine from entering the windows. This changed in the 1930s when desperate, homeless immigrants were arriving. Bauhaus lines were then obscured by ugly balcony enclosures, while giving an extra bedroom.

Bauhaus interiors in Germany were already white, functional and plain. But Tel-Aviv has a hot climate, so rooms had to be as cool as possible. No wall-to-wall carpets and curtains; marble floors instead; and shutters could close windows entirely. And space could be used flexibly, of necessity.

2. The architects’ job was to improve society: housing for working families, trade unions, free clinics.

3. Prefabricated blocks of reinforced concrete, flat roof and sheer façade, no cornices or decoration saved money. Plus a three storey limit.

4. 20+ energetic Bauhaus-influenced architects fled Germany in 1933. Tel-Aviv city council drew on this amazing pool of available talent.

Bauhaus elements were characteristic of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, with some local Tel-Aviv adaptations. Glass was used sparingly, and narrow, horizontal windows appeared on many of Tel-Aviv’s Bauhaus buildings. Vertical windows were used on stairwells.

Along the Mediterranean, balconies increased the movement of breezes and sea views. So overhanging brows blocked direct rays of sunshine from entering the windows. This changed in the 1930s when desperate, homeless immigrants were arriving. Bauhaus lines were then obscured by ugly balcony enclosures, while giving an extra bedroom.

Bauhaus interiors in Germany were already white, functional and plain. But Tel-Aviv has a hot climate, so rooms had to be as cool as possible. No wall-to-wall carpets and curtains; marble floors instead; and shutters could close windows entirely. And space could be used flexibly, of necessity.

first pilotis in TA, designed for Engel House, 1933

garden under house; trees around the building

architect Ze'ev Rechter,

84 Rothschild

The original Bauhaus buildings might have ended up being bulldozed, but a miracle happened: In 1991 the Engineering Dept of Tel-Aviv municipality created a Modern Heritage Preservation under architect Nitza Szmuk. Bauhaus Renovation Foundation organised a Conference for May 1994 for 2,000+ international participants. Along with Dizengoff, Geddes planned a Garden City of wide tree-lined boulevards, small roads with smaller green spots, clean-lined, boxy buildings with little ornamentation and a beach focus. In 2008 Tel-Aviv opened a Bauhaus Museum in Bialik St to display its furnishing designs etc.

Tel Aviv is now home to c4,000 buildings of Bauhaus architecture (2,000 protected under preservation law), the world’s largest collection of Bauhaus-inspired buildings. With the hearty help of Dizengoff, Geddes planned a Garden City of wide tree-lined boulevards, small roads with smaller green spots, clean-lined, boxy buildings with very little ornamentation and a beach focus.

Concrete pilotis/stilts raised the buildings off street level, creating space for green gardens and air flow. As with the balconies, some of the once-open area from stilts were later enclosed. European Bauhaus buildings already had flat roofs, not shingled and slanted roofs. While Tel-Aviv roofs sometimes did not feature roof gardens a la Le Corbusier, they DID serve serve some building residents.

.jpg)

.jpg)

26 comments:

I like the smooth curves on the first few buildings, it saves them from looking like a stack of boxes.

It certainly is an appealing building, Hels.

River

Straight or curved geometric lines are fine for Bauhaus, ditto one colour usually white, ribbon windows and flat roofs. The element that would _not_ be compatible would be decorations.

Margaret

Tel Aviv is a very warm city, spread along the Mediterranean. So white, relatively simple buildings are perfect for beachy homes.

I loved living in Tel Aviv, calling it White City. My favourite building was Cinema Theatre.

Deb,

Thank you. I have added the old name Cinema Theatre to the photo above, and then added the new name Cinema Hotel as well.

Helen hasn't seen the Hotel since the building was sold and repurposed some time during 2010-5, but the Jerusalem Post said the building has retained much of the old-world charm and cinematic accoutrements.

That building is definitely worth looking at. It has great lines and interesting additions like those small circular windows. I bet Tel Aviv is a beautiful city. Sadly I haven't traveled there- at least yet. :) Have a super weekend Hels.

Erika

When the Nazis closed down the Bauhaus Institute of Architecture and Design in 1933, it was a tragedy for Germany but a blessing for Tel Aviv. Dozens of graduates and lecturers left Germany immediately, just as Tel Aviv was starting to boom. The flat roofs and geometrically shaped white buildings were hugely popular. You must visit one day.

The Bauhaus Foundation is a private, non profit exhibition-research centre, dedicated to the conservation and display of Bauhaus art, architecture and design. The primary focus is on the influence and dissemination of the school’s ideas outside of its native Germany, particularly the planning of Tel Aviv City.

21 Bialik St was designed by Shlomo Gepstein in 1934. It neighbours Tel Aviv’s old town hall, Rubin Museum and Bialik Museum, in a unique conservation area that recounts the city’s architectural history. The foundation's exhibition space was inaugurated in 2008 with the display of a unique private collection of utilitarian designs created by renowned Bauhaus teachers and students in the 1920s-1930s. The Foundation now extends its activity to new exhibitions dedicated to art produced by Bauhaus protagonist.

Bauhaus Foundation

I have not seen the Bauhaus Foundation but I am delighted it was placed in a unique conservation area that focused on Tel Aviv's special architectural history. Hopefully the dissemination of Bauhaus' ideas outside of Germany can be well covered, even 80+ years after those first brilliant lecturers and writers. Many thanks.

You might enjoy the following blogs for posts about Bauhaus in Tel Aviv:

1. Tel Aviv – Bauhaus architecture walks around the White City

https://gannet39.com/2020/08/13/7-tel-aviv-bauhaus-architecture-walks-around-the-white-city/

2. Bright Nomad

https://brightnomad.net/travel-photography-bauhaus-architecture-tel-aviv/

3. Bauhaus in Tel Aviv and the World https://slavaguide.com/en/blog/bauhaus-in-tel-aviv-and-the-world

I realky like the external appearance of the Bauhaus style but I wonder if it is dark indoors?

There is a lot of beauty to be found in simplicity and of course the addition of gardens would have added to the beauty of the city. I'm glad it has been recognised as worthy of preservation

kylie

have a look at the room photo I added to the blog post above. It basically follows the same Bauhaus customs as the outside of the building - all one colour usually white; flat roof, no cornices and geometric lines. If residents want to add colour or texture, they can add coloured towels or sheets - anything that doesn't make the inside feel even hotter than it needs be.

What wonderful buildings. I may even prefer the style over Art Deco.

Irina

Many thanks for your previous reading of my posts and your comments, but I won't allow racist or anti Semitic comments in this blog.

The differences between Bauhaus and Art Deco architectures were important. Bauhaus was characterised by its minimalist and abstract design, with emphasis on the use of industrial materials, the exclusive use of geometric shapes and dominated by a white palette. Note its focus on its modernist aesthetic (see Davide Rizzo).

Art Deco adopted a more ornate style, featuring more curved lines, elaborate decorations, vibrant colours and a more detailed approach overall. Note its focus on traditional elements and motifs in Art Deco was quite intricate.

However Art Deco is more popular these days, 100 years after their heydays.

And also 4. The Bauhaus Legacy in Tel Aviv: A Journey from Germany to Israel.

https://medium.com/@ckukur/the-bauhaus-legacy-in-tel-aviv-a-journey-from-germany-to-israel-18b6b12348af

I like the look of these buildings

Jo-Anne

Because Tel Aviv City was still in its developmental phase, the architects had more chances to create a modern cultural history than other cities. They were committed to improve society for the working classes and to build prefabricated blocks of reinforced concrete, flat roof and no wasteful decoration, thus saving money. Plain buildings, but very functional and perfect for hot weather.

I like the ideal of a garden.

peppylady

Agreed!

The original town planning brief was to create a European Garden City for 40,000 citizens, with wide boulevards and large public gardens. Once European citizens understood that the heat was intense AND the population grew x 10 times the suggested maximum, alternative gardens were quickly required. Some buildings added gardens on the flat roof at the top and others raised the building up on pilotis/stilts and used the ground underneath for shortish green plants. Tall trees were often planted around each building.

What beautiful white modern buildings, and such an interesting history. I never read that about Tel Aviv before, thank you for sharing it.

Patricia

Yes indeed.

Tel Aviv is a city I knew very well, especially once my late son and his family lived there. But walking around the streets looking at the public and private architecture is one thing; reading the history in great detail increases our understanding.

Interesting history of those buildings in Tel Aviv. They are easy on the eye and much better than tower blocks. Hopefully they don't get destroyed in the war.

diane

The prefabricated blocks of reinforced concrete in the 1930s were much loved by the architects because of greater building speed, housing effectiveness and cheaper costs. And they looked attractive and modern.

Now the blocks of reinforced concrete may have, sadly, another protective role.

Post a Comment