Napoleon III in Westminster,

erected 1867 and is the oldest surviving plaque

The Society of Arts’ earliest plaques had special patterned borders showing the Society’s name. Plaques were made of bronze, stone and lead, in square, round and rectangular forms, and were finished in brown, sage, terracotta or blue

In 1901 London County Council/LCC took over the scheme and formalised the selection criteria. The LCC’s first plaque commemorated historian Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1903, and then Charles Dickens’ house in Doughty St.

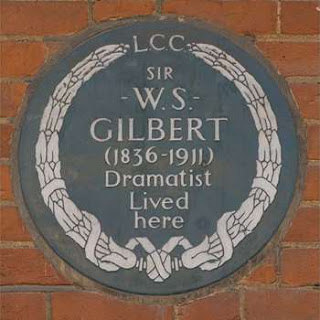

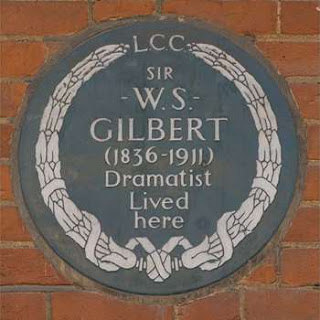

Known as the Indication of Houses of Historical Interest in London, the LCC continued to use the Minton factory, and they developed a highly decorative laurel wreath border with ribbon additions eg see the LCC plaque for librettist WS Gilbert in Sth Kensington. In the 35 years of Society of Arts management, it put up 35 plaques. Barely half of these survive, but John Keats, William Makepeace Thackeray and Edmund Burke’s did.

erected 1867 and is the oldest surviving plaque

A commemorative plaque scheme was first suggested to the House of Commons by William Ewart MP in 1863 and taken up by the Royal Society of Arts in London in 1866. They first commemorated the poet Lord Byron at his Cavendish Square home, but this house was demolished in 1889. So the plaque to Napoleon III in Westminster, erected 1867, is the earliest to have survived.

The Society of Arts’ earliest plaques had special patterned borders showing the Society’s name. Plaques were made of bronze, stone and lead, in square, round and rectangular forms, and were finished in brown, sage, terracotta or blue

In 1901 London County Council/LCC took over the scheme and formalised the selection criteria. The LCC’s first plaque commemorated historian Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1903, and then Charles Dickens’ house in Doughty St.

Known as the Indication of Houses of Historical Interest in London, the LCC continued to use the Minton factory, and they developed a highly decorative laurel wreath border with ribbon additions eg see the LCC plaque for librettist WS Gilbert in Sth Kensington. In the 35 years of Society of Arts management, it put up 35 plaques. Barely half of these survive, but John Keats, William Makepeace Thackeray and Edmund Burke’s did.

WS Gilbert, Plaque erected in 1929

Harrington Gardens, South Kensington, London,

The blue ceramic plaques became standard from 1921 because they stood out best in the London streetscape. They were made by Doulton from 1923-55, with a colourful raised wreath border. In 1938 the modern, simplified blue plaque was designed by a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. This omitted the laurel wreath and ribbon border, & simplified the overall layout, allowing for a bolder spacing and lettering arrangement. After WW2, plaques continued to be unveiled at a regular pace. By 1965, when the LCC was abolished, it had been responsible for creating nearly 250.

The LCC’s successor, Greater London Council/GLC, covered a wider area, now including Richmond and Croydon. From 1966-85, when the GLC was abolished, it had put up 262 plaques, honouring stars like Sylvia Pankhurst women’s campaigner, Mary Seacole Jamaican nurse and Crimean War heroine, and composer-conductor Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. From 1984 on, ceramicists Frank and Sue Ashworth made the blue plaques.

English Heritage took over the scheme in 1986 and didn’t change much. Except to be awarded an official English Heritage plaque, the proposed person must have died 20+ years previously. Its first plaque was in 1986, commemorating painter Oskar Kokoschka at Eyre Court in Finchley Rd, even though Kokoschka had been honoured with a CBE back in 1959. English Heritage’s recent plaques have ranged from Alan Turing to the guitarist-songwriter Jimi Hendrix. Since then English Heritage added 360+ plaques, bringing the total across London to 933.

In 2013–4 government cuts threatened the scheme, but its future was secured by large donations. English Heritage became a charity in 2015 and still manages the scheme.

Harrington Gardens, South Kensington, London,

The blue ceramic plaques became standard from 1921 because they stood out best in the London streetscape. They were made by Doulton from 1923-55, with a colourful raised wreath border. In 1938 the modern, simplified blue plaque was designed by a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. This omitted the laurel wreath and ribbon border, & simplified the overall layout, allowing for a bolder spacing and lettering arrangement. After WW2, plaques continued to be unveiled at a regular pace. By 1965, when the LCC was abolished, it had been responsible for creating nearly 250.

The LCC’s successor, Greater London Council/GLC, covered a wider area, now including Richmond and Croydon. From 1966-85, when the GLC was abolished, it had put up 262 plaques, honouring stars like Sylvia Pankhurst women’s campaigner, Mary Seacole Jamaican nurse and Crimean War heroine, and composer-conductor Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. From 1984 on, ceramicists Frank and Sue Ashworth made the blue plaques.

Alfred Hitchcock plaque

awarded in 1999

awarded in 1999

English Heritage took over the scheme in 1986 and didn’t change much. Except to be awarded an official English Heritage plaque, the proposed person must have died 20+ years previously. Its first plaque was in 1986, commemorating painter Oskar Kokoschka at Eyre Court in Finchley Rd, even though Kokoschka had been honoured with a CBE back in 1959. English Heritage’s recent plaques have ranged from Alan Turing to the guitarist-songwriter Jimi Hendrix. Since then English Heritage added 360+ plaques, bringing the total across London to 933.

In 2013–4 government cuts threatened the scheme, but its future was secured by large donations. English Heritage became a charity in 2015 and still manages the scheme.

Hendrix and Handel homes

museums on upper floors, 23-25 Brook St, Mayfair.

The most recent plaque honoured Isaiah Berlin, philosopher-political theorist-historian of ideas, whose Two Concepts of Liberty is an influential political text. Berlin’s plaque is at his childhood home in Holland Park.Isaiah Berlin, the newest plaque, 2022

33 Upper Addison Gardens, Holland Park

The most recent plaque honoured Isaiah Berlin, philosopher-political theorist-historian of ideas, whose Two Concepts of Liberty is an influential political text. Berlin’s plaque is at his childhood home in Holland Park.

33 Upper Addison Gardens, Holland Park

Is it too high for pedestrians to read?

I studied Australian history in primary school, but only British Empire, European and Russian history in high school & university. So when historians called for a Blue Plaque Programme in NSW years ago, I thoroughly agreed.

The home in which children’s author May Gibbs created the bush fairy tales of Snugglepot and Cuddlepie has now been recognised. Nutcote Cottage, Gibbs’ former studio on Sydney’s North Shore, is one of the first buildings in NSW to display a blue plaque modelled on London’s programme, and funded through Heritage NSW.

Premier Mr Perrottet said the Blue Plaque programme would successfully unlock the stories of NSW’s history, promoting the significance of key heritage places and people from all cultures. Artist Brett Whiteley and Indigenous champion Charles Perkins were two of the initial figures recognised by 700+ public nominations. In Apr 2022 NSW’s Heritage Minister Don Harwin announced 17 Blue Plaques, selected from 750 nominations made in Nov 2021 by community organisations and local councils. They’ll be installed across NSW later in 2022. Plaques will adorn the ex Registrar-General’s Building in Sydney designed by architect Walter Liberty Vernon, and heritage-listed Caroline Chisholm Cottage East Maitland, a hostel for homeless migrants.

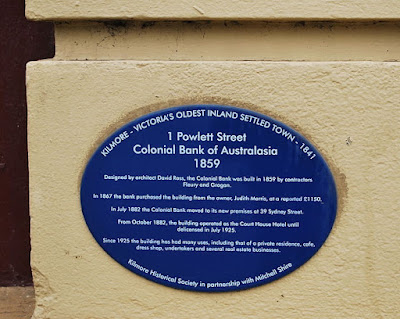

Blue plaques are also available to owners of sites listed in the Victorian Heritage Register. In 1999 the Mechanics Institute of Victoria Historical Plaques Programme planned to publicise the history of these Institutes across Victoria. The original Mechanics Institute was built in 1842 in Melbourne. The Athenaeum Building, with the statue of Athena on the parapet, was completed in 1886 to a design by architects Smith & Johnson, and is registered by the Heritage Council. Werribee Railway Station was completed in 1857 as part of the Geelong Melbourne Railway, Australia’s first country railway. It has retained its original walls, platform and cellar, and is registered. The Colonial Bank of Australasia building in Kilmore, later the Court House Hotel, is also easily identified now.

The Colonial Bank of Australasia building

Kilmore, Victoria

I studied Australian history in primary school, but only British Empire, European and Russian history in high school & university. So when historians called for a Blue Plaque Programme in NSW years ago, I thoroughly agreed.

The home in which children’s author May Gibbs created the bush fairy tales of Snugglepot and Cuddlepie has now been recognised. Nutcote Cottage, Gibbs’ former studio on Sydney’s North Shore, is one of the first buildings in NSW to display a blue plaque modelled on London’s programme, and funded through Heritage NSW.

Premier Mr Perrottet said the Blue Plaque programme would successfully unlock the stories of NSW’s history, promoting the significance of key heritage places and people from all cultures. Artist Brett Whiteley and Indigenous champion Charles Perkins were two of the initial figures recognised by 700+ public nominations. In Apr 2022 NSW’s Heritage Minister Don Harwin announced 17 Blue Plaques, selected from 750 nominations made in Nov 2021 by community organisations and local councils. They’ll be installed across NSW later in 2022. Plaques will adorn the ex Registrar-General’s Building in Sydney designed by architect Walter Liberty Vernon, and heritage-listed Caroline Chisholm Cottage East Maitland, a hostel for homeless migrants.

Blue plaques are also available to owners of sites listed in the Victorian Heritage Register. In 1999 the Mechanics Institute of Victoria Historical Plaques Programme planned to publicise the history of these Institutes across Victoria. The original Mechanics Institute was built in 1842 in Melbourne. The Athenaeum Building, with the statue of Athena on the parapet, was completed in 1886 to a design by architects Smith & Johnson, and is registered by the Heritage Council. Werribee Railway Station was completed in 1857 as part of the Geelong Melbourne Railway, Australia’s first country railway. It has retained its original walls, platform and cellar, and is registered. The Colonial Bank of Australasia building in Kilmore, later the Court House Hotel, is also easily identified now.

Kilmore, Victoria

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

17 comments:

Caroline Chisolm was NSW's first person to deserve and get a Blue Plaque. It went onto her East Maitland Cottage, dating back to the 1840s.

Deb

Agreed. Caroline Chisholm was a pioneering humanitarian who fought to improve conditions for immigrants. Until you mentioned her, I had no idea that Chisholm converted the cottage into an important immigrant hostel.

I might mention two more deserving NSW Blue Plaques - the author and illustrator May Gibbs, and the children's author Ethel Turner.

The New South Wales government has been accused of politicising history after announcing the first 17 successful public applications for the state’s new blue plaque scheme. The $5m program has been modelled on a similar scheme in the UK for more than a century to remember notable people and places.

It will see circular blue plaques placed on buildings where historical figures lived or worked, or where major events occurred. Sydney artist Brett Whiteley and Indigenous activist Charles Perkins were among the initial figures to be recognised from more than 700 nominations by members of the public across NSW.

But none of the 17 plaque locations, revealed on Monday by the NSW heritage minister were in Labor-held electorates.

I'd like to see a state scheme here rather than the ad hoc system currently in use. There are so many buildings deserving blue plaques. I was thinking the other day as we passed by the Beaconsfield Parade house of Madam Brussels that it should have a plaque.

This is a great idea. I live in a house over 100-year-old as well. I do wonder the history of the house I reside in.

Guardian

I don't think Labor electorates were deliberately ignored, but I do believe the "type" of individuals awarded affected the location of their family homes. So if the awardees were largely supreme court judges and leading bankers, they would have lived in very different locations from awardees who had been Olympic boxers, AFL footballers or union leaders.

Andrew

Heritage Council Victoria said the plaques are available to owners of places and objects listed in the Victorian Heritage Register, a way of highlighting Victoria’s diverse heritage places, and the stories and history behind them. _All_ places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register are _automatically_ entitled to a blue plaque. Thus they invited all owners of registered places and objects to participate in the blue plaque program.

Unless the Heritage Register did its own very careful analyses, the blue plaque system does sound a bit ad hoc, doesn't it?

roentare

oh I agree with you totally. It is like finding all the vital information about your grandparents - you have to do a lot of research.

If you find your home used to be nasty brothel and drug centre, just give it a good wash and a new name :) But if you find your home was the site of an important family or vital event, perhaps apply for a blue plaque yourself. Then prepare for tourists and school groups standing in front of the front gate, taking photos :)

Italian-born Thomas Fiaschi (1853 – 1927) graduated with the degrees in medicine and surgery in Florence. He moved to Sydney at 22 and became honorary surgeon to the Governor General, and later consultant surgeon in Sydney Hospital. With the Great War, Dr Fiaschi went to England as commanding officer of Australian General Hospital. His efforts for Australia were innovative and untiring, thoroughly deserving his blue plaque.

Dr Joe

I agree with you, even though I didn't know about your man before today.

Dr Thomas Fiaschi's experiences and learning as a war surgeon were well documented in the academic journals and lectures. His innovations rightly earned him a knighthood from King Umberto. Returning to Australia in late 1917, he joined the Army Medical Corp Reserve and retired in 1921 as Honorary Brigadier General.

Boa tarde e bom final de semana minha querida amiga. Parabéns pelo seu trabalho maravilhoso e aula de história.

Luiz

thank you. Are you familiar with this sort of programme in your own country or any neighbouring countries?

So glad Australia has adopted this scheme. It's surprisingly interesting to notice who lived where, isn't it? (Often they live in rather improbable places, in my experience) Although I live not far from Eyre Court, I have never seen Kokoschka's plaque. (and I would not have expected him to live there, in fact). I was thrilled to walk past a plaque the other day to David Devant. I wish I had had the chance to see some of these famous stage magicians of the past. And I was very surprised to see a plaque to JOhn Betjeman in Cloth Court, a tiny ancient little alley near Charterhouse. It didn't seem quite his style at all - I'd have thought he'd have chosen somewhere Victorian and in-your-face to live.

Jenny

it is such fun, yes. I loved the blue plaques I saw when we lived in the UK, and if someone seemed very interesting, I did a whole lot of follow-up research after. For example I had known a lot about Kokoschka's art, but hadn't remembered his years living in Britain.

https://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com/2019/07/alma-schindler-mahler-musical-talent.html

Hopefully the blue plaques will be as exciting and useful in Australia.

I work just off Bridge Road in Richmond and love all the plaques on the shops that give an idea of history . Makes a walk along Bridge Road a real treat .

mem

Agreed. Spouse and I play a game every time we see a Blue Plaque: who knows the right answer to "the type of architecture", "the decade and purpose of the building" and "who might the architect have been"? As you say, the plaques give a wonderful sense of history to buildings we have seen for yonks.

Walk the streets of London and chances are you’ll soon come across an English Heritage Blue Plaque commemorating someone famous. There are now more than 990 Blue Plaques in London, commemorating everyone from diarist Samuel Pepys to writer Virginia Woolf and comedian Tony Hancock.

London Explained – English Heritage’s Blue Plaques

Post a Comment