Arts Centre Melbourne

Felix Bischofswerder (1922-2012) was born in Berlin. He received his first music lessons from his father, the Jewish cantor Boas Bischofswerder in a leading Berlin synagogue. Felix's German heritage also greatly impacted his music. His father had also been a composer in Schoenberg's musical circle, and from primary school Felix had acted as copyist for his father. Synagogue music appeared in his use of the Hebraic modes in early works. This conveyed to him the spiritual and musical traditions of Judaism, including the worlds of Moses Mendelssohn and Arnold Schönberg.

After the Nazis took power, the family escaped to London in 1933 where his father again worked as a cantor. Felix finished high school, studied architecture and art history, then attended the Guildhall School of Music. In June 1940 he was arrested as an Enemy Alien and interned, then accompanied his father who was deported to Australia on the ship Dunera. While his father sickened from the miserable conditions aboard and in the Australian internment camps Hay and Tatura, Felix contributed to the musical life of the internees by writing works by George Frideric Handel and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart known for the camp orchestra from memory. Through style copies, he worked his way self-taught to his own compositions. The two years in the Tatura camp, where he also wrote a treatise on the history of Jewish music, he later called his most important school.

Felix was 18 when he was confined on the Dunera in 1940, so his fine works, including his symphonies, chamber music, choral works and operas, were all written in Australia.

In order to support his sick father financially, Felix volunteered for the Australian Army in 1943. Whilst in the army, he married Mena Waten, sister of novelist Judah Waten, who encouraged him in his leftist politics. Judah and Mena were my mother’s first cousins, so my musically skilled mother warmly welcomed Felix into the family.

When his father died in 1946, Felix ended his military service and received Australian citizenship as Werder. Although another musical refugee Werner Baer arranged for him to work as a music arranger, Felix had to take up a teacher training course in Melbourne in 1947 to gain a reliable income. He earned his living as an adult education teacher, and as choirmaster of the Melbourne Hebrew Congregation.

Public recognition and performance were at first hesitant; Werder’s orchestral Balletomania (1940) had to wait 8 years for its first performance. Violinist Szymon Goldberg, then living in Sydney, sent Werder’s music to the conductor Eugene Goossens, who then performed Balletomania in Oct 1948 with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Encouraged by Goosens and fellow-conductor Walter Susskind, Werder had the support of the concert organisation Musica Viva Australia, founded in 1945 by Richard Goldner, a Jewish Viennese-trained violist refugee. It became the world's largest entrepreneurial chamber music organisation.

Kisses for a Quid by Felix Werder

After the Nazis took power, the family escaped to London in 1933 where his father again worked as a cantor. Felix finished high school, studied architecture and art history, then attended the Guildhall School of Music. In June 1940 he was arrested as an Enemy Alien and interned, then accompanied his father who was deported to Australia on the ship Dunera. While his father sickened from the miserable conditions aboard and in the Australian internment camps Hay and Tatura, Felix contributed to the musical life of the internees by writing works by George Frideric Handel and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart known for the camp orchestra from memory. Through style copies, he worked his way self-taught to his own compositions. The two years in the Tatura camp, where he also wrote a treatise on the history of Jewish music, he later called his most important school.

Felix was 18 when he was confined on the Dunera in 1940, so his fine works, including his symphonies, chamber music, choral works and operas, were all written in Australia.

In order to support his sick father financially, Felix volunteered for the Australian Army in 1943. Whilst in the army, he married Mena Waten, sister of novelist Judah Waten, who encouraged him in his leftist politics. Judah and Mena were my mother’s first cousins, so my musically skilled mother warmly welcomed Felix into the family.

When his father died in 1946, Felix ended his military service and received Australian citizenship as Werder. Although another musical refugee Werner Baer arranged for him to work as a music arranger, Felix had to take up a teacher training course in Melbourne in 1947 to gain a reliable income. He earned his living as an adult education teacher, and as choirmaster of the Melbourne Hebrew Congregation.

Public recognition and performance were at first hesitant; Werder’s orchestral Balletomania (1940) had to wait 8 years for its first performance. Violinist Szymon Goldberg, then living in Sydney, sent Werder’s music to the conductor Eugene Goossens, who then performed Balletomania in Oct 1948 with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Encouraged by Goosens and fellow-conductor Walter Susskind, Werder had the support of the concert organisation Musica Viva Australia, founded in 1945 by Richard Goldner, a Jewish Viennese-trained violist refugee. It became the world's largest entrepreneurial chamber music organisation.

Q Theatre Guild, 1961

Victorian Collections

Werder's influence grew considerably when he became music critic of the top newspaper The Age in Melbourne in 1960. His criticism, taking European culture as a baseline, earned him as much respect as disagreement. Werder was a leading figure in the Australian avant-garde, but has always attached great importance to his European roots. His extensive catalogue of works ranged from chamber, choral and orchestral music to 8 operas.

In 1965 Sydney Symphony Orchestra performed Elegy for Strings at the Royal Festival Hall in London, then Fritz Rieger performed Violin Concerto (1966) in Melbourne. Only by the late 1970s was Werder's influence declining, even though he still gathered a crowd of keen students around him.

He could no longer go on major journeys after a stroke in 2000, but remained active as a composer until the end. In 2003-4 Albrecht Duemling used the National Library of Australia’s music collection to document both the personal experiences of refugee musicians and their professional contributions to Australian music. In his new book The Vanished Musicians: Jewish refugees in Australia 2011, he discussed the reception Australia offered to German-speaking refugee musicians who arrived here from 1933 on.

In Feb 2012, his 19th string quartet, The H-Factor, was premiered at a concert for his 90th birthday. Felix Werder died in 2012 in Melbourne.

c9,000 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany settled in Australia during 1933-45. Australia should have felt blessed when world-famous Jewish musicians arrived on our shores. Consider piano virtuoso Jascha Spivakovsky and his trio (with Nathan Spivakovsky and Edmund Kurtz), Artur Schnabel, Richard Tauber and Yehudi Menuhin, and the conductor Maurice Abravanel. The composer and basoonist George Dreyfus was even younger when he left Germany in 1938, so he did all his musical studies in Australia. How tragic that these Jewish refugees, fleeing Nazism at home, were declared enemy-alien-Germans in Australia. Most were imprisoned in rural camps, in Hay and Tatura.

So the modern viewer asks if the Musicians’ Union of Australia tried to save these professional musicians and composers in the late 1930s. Apparently not. The Musicians’ Union felt it was hard enough to find full-time work for real Australian citizens and applied pressure on the Immigration Department to turn foreign musicians away from our shores or put them in non-musical jobs. If a talented musician wanted Australian citizenship in 1939, he was advised call himself a factory worker or shoe maker ☹ Most did.

In 1965 Sydney Symphony Orchestra performed Elegy for Strings at the Royal Festival Hall in London, then Fritz Rieger performed Violin Concerto (1966) in Melbourne. Only by the late 1970s was Werder's influence declining, even though he still gathered a crowd of keen students around him.

He could no longer go on major journeys after a stroke in 2000, but remained active as a composer until the end. In 2003-4 Albrecht Duemling used the National Library of Australia’s music collection to document both the personal experiences of refugee musicians and their professional contributions to Australian music. In his new book The Vanished Musicians: Jewish refugees in Australia 2011, he discussed the reception Australia offered to German-speaking refugee musicians who arrived here from 1933 on.

In Feb 2012, his 19th string quartet, The H-Factor, was premiered at a concert for his 90th birthday. Felix Werder died in 2012 in Melbourne.

c9,000 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany settled in Australia during 1933-45. Australia should have felt blessed when world-famous Jewish musicians arrived on our shores. Consider piano virtuoso Jascha Spivakovsky and his trio (with Nathan Spivakovsky and Edmund Kurtz), Artur Schnabel, Richard Tauber and Yehudi Menuhin, and the conductor Maurice Abravanel. The composer and basoonist George Dreyfus was even younger when he left Germany in 1938, so he did all his musical studies in Australia. How tragic that these Jewish refugees, fleeing Nazism at home, were declared enemy-alien-Germans in Australia. Most were imprisoned in rural camps, in Hay and Tatura.

So the modern viewer asks if the Musicians’ Union of Australia tried to save these professional musicians and composers in the late 1930s. Apparently not. The Musicians’ Union felt it was hard enough to find full-time work for real Australian citizens and applied pressure on the Immigration Department to turn foreign musicians away from our shores or put them in non-musical jobs. If a talented musician wanted Australian citizenship in 1939, he was advised call himself a factory worker or shoe maker ☹ Most did.

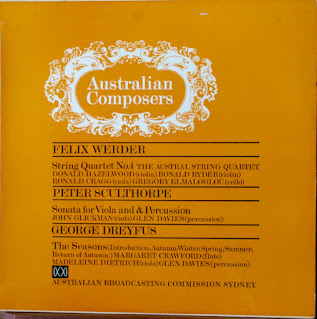

Discogs, 1969

Australian Composers

Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1970

Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1970

Discogs

Conclusion

The refugees were initially received as Enemy Aliens but many of them remained here and made a significant impact on multicultural Australia. Albrecht Duemling's book The Vanished Musicians: Jewish Refugees in Australia traced the difficult journey of 100 displaced orchestral performers, conductors and composers who’d sought refuge from Nazism. See Werder’s and others’ biographies in Duemling’s book.

The Vanished Musicians: Jewish Refugees in Australia

by Albrecht Dümling, 2016

by Albrecht Dümling, 2016

Amazon

.jpg)

8 comments:

Germany had the finest cultural communities in the world, yet they knowing destroyed it all through exile or death. Australia simply got lucky, saving some of these cultural stars

Boas Bischofswerder composed his Phantasia Judaica on the Dunera for four voices, and this remains the only surviving creation from that journey.

Werner Baer and Walter Wurzburger were on the Queen Mary from Singapore and then held in the Tatura camp. Baer’s aspiration had been to conduct opera. After he joined the Australian army on his release from the camp, in 1942, he continued to write song settings, many of which are published. After the war and relocation to Sydney, Baer was approached by the Austrian-Jewish modern dance exponent, Gertrud Bodenwieser, to write work for her company.

Walter Wurzburger began composing seriously in the Tatura camp. He was from a musical family and having already studied jazz with the Hungarian composer Mátyás Seiber in Frankfurt. In Australia he freely explored his own voice, creating a string trio and a song set to the moving words of Friedrich Nietszche’s poem Vereinsamt (Lonely).

George Dreyfus was sent on a Kindertransport to Melbourne, where he lived at the Larino home for refugee children. Dreyfus trained as a bassoonist, and later moved into composition, composing numerous scores for film and television, the most famous being the theme song for the 1974 TV series Rush.

Dr Joseph Toltz,

Sydney Conservatorium of Music.

LMK

I had that exact thought when the Nazis closed Bauhaus Academy in 1933. They knew that German artists and architects were the finest professionals anywhere. But from 1933 on, the Nazi regime was sooo fixated on ending ANY foreign and Jewish influences of cosmopolitan modernism, they were quite happy to end Germany's cultural leadership of the world.

Joseph

thank you for reminding us that these musical professionals came out of chaos in Central Europe, lost their families, had to learn a new language and were stuck in internment camps for years. Yet they were so committed, brave and talented, their musical careers made a huge difference to post-war Australia.

I hope readers locate Albrecht Duemling's book: The Vanished Musicians: Jewish Refugees in Australia.

And so it goes on with us demonizing refugees without considering the amazing reservoir of talent , strength and determination which we throw away in so doing .Of course not everyone is exceptional but many are as to have gotten on a boat and got to Christmas island shoes a certain determination wand strength of character which could surely be put to good use .

What an amazing background you have Hels . Thanks for this post .

mem

for a country that has a relatively small indigenous population, everybody else was born overseas or the descendants of so-called foreigners. So I am still angry that at every opportunity in the 20th century when Australia could have saved thousands of victims of persecution, our politicians made it clear that Australia HAD to remain British and white. Even in the 21st century, I am not sure that we have become any more sensitive to human needs.

Felix Werder was just one of the German, Austrian and Italian prisoners of war locked up in camps at Hay and Tatura, including the Dunera Boys. You are right that not all of them were exceptional, but they were desperate to create quality lives for themselves (and their eventual families) in their new homeland - in literature, music, art, sport, medicine, academe etc etc.

So, Felix Werder was the son of a cantor! That means a lot to me as I'm a great fan of cantorial music. My late parents were fans too.

I like it that Werder attached in his music importance to his european roots. I consider these roots priceless, despite Germany and the Nazis.

DUTA

Felix Werder had the best _ever_ training in Chazanut. Not only did the young man learn in his father's famous Berlin Synagogue... his dad also wrote and practised his liturgical composing at home. So it might have been surprising to us that Felix later became famous in Australia as a composer and teacher at the cutting edge of the avant-garde. Not to him, however. It seems he believed music was on a very long term continuum, from the religious to the Renaissance to the Modern and the Postmodern.

Post a Comment