Albert Camus (1913-1960) was born in Algeria in 1913 with no father and a sick mother. So they moved to Camus' grandmother's apartment in Algiers, for the lad to receive a good education. Tertiary education was interrupted and delayed by TB but he did eventually go back to uni in 1930. Mixing with young, progressive intellectuals, he co-founded the Workers' Theatre and co-wrote a play for their theatre. The group also produced plays by Dostoevski and other established playwrights, especially chosen to appeal to the workers of the city.

Travelling to Europe first became possible for Camus in 1936, and one year later his first collection of essays was published. In 1938 Camus became a journalist for a newspaper called the Alger-Republicain, clearly hoping for independence from France (which was not achieved until 1962).

Camus left Algiers in 1940 for Paris, seeking work as a reporter for the progressive press. But 1940 was the worst time in French history for an outsider to arrive, so he returned home to Algeria. He found a teaching position in Oran, writing openly against war in Europe - this put him in danger due to the political right's rise in power in both France and Algeria. Having been declared a threat to national security later in 1940, this young man in his 20s was advised to leave Algeria as quickly as humanly possible.

Of course back in Paris he found the German army had taken the French capital and most of Northern France.

Travelling to Europe first became possible for Camus in 1936, and one year later his first collection of essays was published. In 1938 Camus became a journalist for a newspaper called the Alger-Republicain, clearly hoping for independence from France (which was not achieved until 1962).

Camus left Algiers in 1940 for Paris, seeking work as a reporter for the progressive press. But 1940 was the worst time in French history for an outsider to arrive, so he returned home to Algeria. He found a teaching position in Oran, writing openly against war in Europe - this put him in danger due to the political right's rise in power in both France and Algeria. Having been declared a threat to national security later in 1940, this young man in his 20s was advised to leave Algeria as quickly as humanly possible.

Of course back in Paris he found the German army had taken the French capital and most of Northern France.

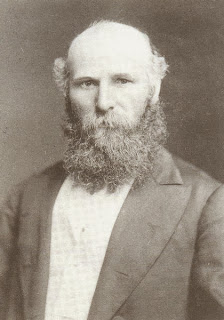

Camus (left) and Sartre, Paris

Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Albert Camus first met in June 1943, at the opening of one of Sartre's plays. Camus’ recently published novel The Stranger, was a big success, so they certainly knew who he was. Camus wanted to meet the French novelist, playwright philosopher whose fiction he had reviewed years earlier and who had just published a long article on Camus' own books. In November 1943, Camus moved to Paris to start working as a reader for his (and Sartre's) publisher, Michel Gallimard, and the trio’s friendship warmed. They met at Café Flore, Sartre and Beauvoir’s favourite drinkery and office-away-from-home.

In 1943 Camus joined Combat, an illegal resistance cell and newspaper that had been founded in 1942 for sabotage of the German war-machine. Camus helped by smuggling news of the war to the Parisian public via copies of the Combat paper. He became its editor in 1943, and held this position for four years. His articles often called for action in accordance to strong moral principals, and it was during this period of his life that he was formalising his philosophy.

If modern readers know only one of Camus’ novels it would be The Stranger (1942) - on the theme of the alienated outsider. His political history and experiences in occupied France led him to search for a way to address moral responsibility. He expressed himself in works like Letters to a German Friend (1945), which was published with other political essays, in Resistance, Rebellion and Death (1960). Part of what made Camus different from other philosophers was his fascination for and acceptance of contradiction. But that is exactly what made Camus difficult to read.

Picasso's studio, 1944

I am very grateful to The Art Blog for this photograph by Brassaï. It showed important cultural figures gathered in 1944 in Paris after the private production of Picasso's surrealist play, Desire Caught By the Tail. Jean-Paul Sartre was seated on the floor with his pipe; Simone de Beauvoir held a book; Camus was staring at the dog; Picasso was in the middle; his paintings in the background.

By the end of the war, Camus had become a leading voice for the French working class and social change. In 1946 he visited Lournarin in Province with three fellow writers and decided to stay. He rented a house in this beautiful town that reminded him of Algeria, but could not afford to buy one until his Nobel Prize money arrived in 1958. Daughter Catherine now lives in the family home in Rue de l'Eglise, complete with its large terraces, rose filled gardens and views of the distant hills. But today the street is called Rue Albert Camus.

In 1949 Camus had a relapse of his TB and turned to writing in his bedroom. When he recovered in 1951 he published The Rebel, a text on artistic and historical rebellion, in which he laid out the difference between revolution and non-violent revolt. He criticised Hegel's work, accusing it of glorifying power and the state over social morality. Camus preferred his moderate philosophy of Mediterranean humanism to violence. But the attacks on Hegel and Marxism in The Rebel had an alienating effect on Camus' peers and leftist critics. After Camus attempted to defend himself in a letter to the publication, the editor of Les Temps Modernes (Jean-Paul Sartre!!) published a very long, attacking letter in response. This marked the end of the two philosophers' friendship… what a tragedy for Camus.

I know Camus and Sartre had been intimate friends and collaborators until that point. But I cannot discover whether Camus and de Beauvoir had had a friendship, separate from the occasional coffee with the three of them together.

The Camus house in Lourmarin, Provence

Camus began to write for l'Express daily newspaper in 1955, covering the Algerian war. The violence was escalating in Algeria with the arrival of French troops, and Camus was devastated. He organised a public debate between Muslims and the Front Français, which fortunately went without incident. Then Camus came back into favour with intellectual circles in 1956 with the publication of his novel The Fall.

Throughout his life, Camus continued to work for the theatre, taking on the various roles of actor, director, playwright and translator. State of Siege (1948) and The Just Assassins (1950) were two of his clearly political plays. He also did successful stage adaptations of novels like William Faulkner's Requiem for a Nun (1956) and Dostoyevsky's The Possessed (1959).

Melville House blog noted that the American FBI tracked Sartre and Camus via surveillance, theft, wire-tapping and eavesdropping. Apparently FBI agents were pursuing Camus, in particular, because he had been a member of the anti-German resistance in France. Needless to say Camus never returned to the USA after his monitored visit in March 1946.

J Edgar Hoover may have been furious but he could not stop Camus receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature for his essay Réflexions Sur la Guillotine in 1957. In fact the Nobel committee particularly cited the author’s persistent efforts to illuminate the problem of the human conscience in our time! It was largely as a writer of conscience and as a champion of imaginative literature as a vehicle of philosophical insight and moral truth that Camus was honoured after WW2 and is still admired today.

In 1960, Camus and his close friend and publisher Michel Gallimard died in a car accident near the French city of Sens while returning to Paris. What a terrible shame that Camus a) died so young and b) died before he could see Algerian independence declared. Nonetheless visitors can see where his memory lives on. There is a Camus trail in Province that includes his family home in Lourmarin, his beloved football ground, the restaurant that he used as his office, the gardens where he wrote standing up, the chateau where he first lived in Lourmarin and the cemetery where both Camus and Francine were buried.

.jpg)