Yosl Bergner was born in Vienna in 1920, and was raised in Warsaw. With rampant anti-Semitism in Europe, the Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonisation was formed in July 1935, to search for a potential Jewish home land. Soon afterwards a pastoral firm offered the League c16,500 square ks in the Kimberleys, stretching from the north of Western Australia into the Northern Territory. The plan ultimately failed, but for a time, the idea was at least interesting. Bergner's father, Melech Ravitch, became involved in a serious investigation of the Kimberleys, and thus the Bergner family moved to Australia.

16 year old Yosl left Poland with Yosl Birstein, who became a novelist. Together the teenagers travelled to Australia, arriving in 1937 when this country was still in the grip of the Depression. He thus belonged to the generation of people uprooted from home and forced to build a life elsewhere. Even safely in Australia, Bergner struggled to survive. He worked in unskilled jobs in Carlton factories, while studying painting at Melbourne’s National Gallery Art School.

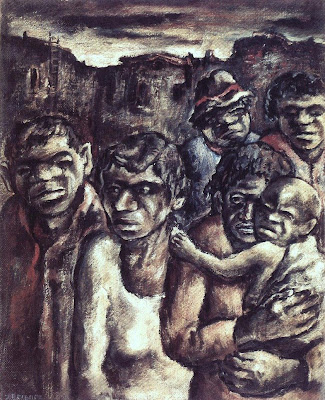

Father and Sons, 1943

Father and Sons, 1943From this inauspicious beginning, Klepner asks, how could such a raw teenage new comer affect the course of art events? In Melbourne from 1937-48, Bergner befriended many of the local artists who now epitomise modern Australian art: Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, John Perceval and Arthur Boyd. The men socialised together.

Friendship with artist Arthur Boyd introduced a new avenue of Bergner influence. Klepner suggests that Boyd came from the most stable back ground of all the 1940s artists and had never met anyone like Bergner with his deprivation and persecution. Boyd noted that Bergner’s great influence was his expressionist style. Yosl introduced him to writers like Dostoyevsky & Kafka. Bergner’s profound commitment to humanitarian values reinforced Boyd’s own social conscience. Some of the urban paintings of 1938 and 1939 showed Boyd’s new direction: dark backgrounds, shrouding heavily outlined heads distorted by anxiety or cruelty, or some other existential, deep turbulence. Boyd noted that Bergner encouraged them to go beyond their traditional landscape style; he introduced them to social commentary about the human condition, thus changing Australian art.

Adrian Lawlor returned from WW1 in 1919 & moved with his wife to Warrandyte where they lived for 30 years. Bergner was a frequent visitor at this home. Lawlor & George Bell strongly resisted the proposal to form a conservative Australian Academy of Art in 1937 and next year set up the opposing, progressive Contemporary Art Society with Lawlor as secretary. Lawlor’s 1937 book and 1939 pamphlet dealt well with the controversy; he was a guide-lecturer at the 1939 Herald Show of French/British Contemporary Art and spoke on modern art at meetings.

Young Tucker looked upon his art as a hobby. It wasn't until meeting Russian Danila Vassilieff who arrived in Melbourne in 1937 and Yosl Bergner in 1938 that Tucker changed his mind. These foreign artists and their unsettling depictions of the anguish of the most oppressed elements of Australian society had a strong impact on Tucker. He soon began to investigate and create the trauma, insecurity and anxiety produced by the Depression and the war. The two Europeans’ experience convinced Tucker that, despite his background and his poverty, he could also make a career out of his work.

It was at this point that Tucker’s talent was spotted by Sunday and John Reed, and his involvement with the Heide homestead and his association Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd and Joy Hester, who became his wife. He felt for the first time, despite the differences of ideologies and beliefs, very much a part of a like-minded group. Tucker wrote for the publication Angry Penguins, the principal outlet for the expression of avant-garde ideas between 1941-6.

Still Life c1941 (Ian Potter) shows his Surrealist influence. The domestic utensils of the house become alive, yet they remain sharpish. Noel Counihan's approach to light and dark was said to be influenced by Bergner's Still Life, a rendering of vegetables lying on a white tablecloth that melds with the European snow. "I was the first expressionist in Australia," Bergner wrote in What I Meant to Say, in 1997. "I brought expressionism to Australia without knowing it." Inspired by European modernism his strong social-realist paintings were influenced (politically or in painting style) by French artists like Daumier.

Bergner's influence on Tucker, Noel Counihan, Arthur Boyd and Vic O'Connor was great. It was not just the style and mood of Bergner's paintings - the dark, glowering eerie cityscapes where the dispossessed, the victims and the loners wander. The Australian born artists clearly loved the idea of a marginalised refugee making it in art.

Of course Bergner wasn't the only source of Europeanisation. Exhibitions of modern art from Europe and America had a great effect on the local scene. In 1939 the Herald Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art (aka Degenerate) in the Melbourne Town Hall assembled canvases that included many of the best modernists in France and Britain. Then in 1941 the Contemporary Art Society held its famous exhibition, bringing together works testifying to the dynamic changes that had taken place in Australian painting since the 1930s. Two triumphs for progressive art.

Aboriginals in Fitzroy, 1941

Aboriginals in Fitzroy, 1941Yet of the generation of artists that called themselves the Angry Penguins, Bergner was arguably one of the least appreciated! Bergner was probably unprepared for the plight of many struggling Australians. Yet he felt a strong connection between the suffering of people everywhere, whether they were the Jews in Central and Eastern Europe, dispossessed blacks in central Australia or hungry children in Carlton. Among his subjects of that time were highly sympathetic depictions of indigenous Australians eg Aborigines in Fitzroy 1941 (SA Gall).

He painted images which were drawn from his experience of hunger; views of a sad urban environment, inhabited by refugees and slum dwellers. Klepner’s book has very moving, dark works like Citizen and The Pumpkin Eaters 1939-42, now in state galleries.

The empathy that Bergner displayed in his art attracted immediate attention, according to Klepner, and inspired many young Melbourne artists during the 1940s. Russian artist Danila Vassilieff also arrived in Melbourne in 1937 and met Bergner and Tucker in 1938. These meetings inspired Tucker to examine his values and to focus on the pain of the Depression and of war. Bergner's influence on Noel Counihan was just as important; Klepner suggests that Counihan's approach to light and dark was affected by Bergner’s expressionism. Tucker, Bergner, Counihan and Vassilieff all joined the newly formed Contemporary Art Society, to give voice to art not accepted by the establishment and to influence the future direction of Australian art.

The Pie Eaters 1940 was shown at Melbourne's Contemporary Art Society Annual Exhibition in 1941. Appropriately the exhibition was entitled: Art and Social Commitment: an end to the city of dreams 1931-1948. Pie Eaters portrayed 2 refugees in a dark, barren environment, enclosed by the wall behind them. They neither speak nor look at each other, as each is lost in their own world. Despite the title of the painting, there is no pie to be seen, just a bare table, an empty plate, a bottle and continuing hunger. Perhaps it illustrated a very personal and passionate response to the artist’s own poverty.

In the 1940s he was a homeless painter. Bergner’s association with the Australian Jewish community was predominantly through Kadimah and the Yiddishists. He became very friendly with writers Pinchas Goldhar, Judah Waten and Yosl Birstein. Fortunately they provided food!

Tocumwal, 1944

Tocumwal, 1944During WW2, Bergner enlisted in the Australian Army Labour Company at Tocumwal NSW 1941-6. He worked with other Friendly Aliens who had been refugees from Axis countries. Drawing on personal experience, he evoked a mood of dejection and exhaustion eg Tocumwal, Loading the Train 1944. The bleak palette of muted browns added to the atmosphere of gloom. The 4 anonymous figures, their bodies slumped dejectedly, had survived another day of endless loading and unloading goods trains for the war effort. Bergner later won a Commonwealth Rehabilitation Scholarship, to return to studies at the National Gallery Art School.

For Albert Tucker WW2 was also an experience that violated the social and moral stability of urban Australia. He was disturbed by the live-for-the-day mentality that pervaded the city with the influx of servicemen on leave. Victory Girls 1943 presents a grotesque night image of two young women accepting the advances of drunken soldiers. In Flinders St At Night 1943, we note the nightmarish qualities of a woman dancing with a death mask and of 2 trumpeters playing away. The painting seems to be speaking out against the immense slaughter of human life and the distorted social relations produced by the war.

Bergner may have kept his sense of humour, but his work was often dark and despairing. There were hints of optimism eg the recurring motif of the ladder, symbol of hope. But darkness was ongoing. Two Women 1942, one black and one white, had an air of resignation. Father and Sons 1943 was beyond despair. Only Looking Over the Ghetto Wall 1943 suggested vague hopefulness, unfulfilled hopefulness (all three in the NGV).

Bergner was only in Australia until 1948, before leaving permanently for Israel. Yet it was Bergner who showed that art was not merely a reflection of Australian society; instead it could be an instrument in its very shaping. In his 11 years here, Bergner became politically more involved and his social criticism sharpened.

Over the Ghetto Wall 1943

Over the Ghetto Wall 1943He left Australia in 1948, travelling first to Paris and then to Israel in 1951. It is said that he became an Israeli without shedding his Jewish cosmopolitan/refugee identity, an identity he zealously guarded in Israel’s melting pot of the 50s and 60s. Even after the state was established, Bergner’s Israeli works were filled by the trauma of the refugee. Eugene Kolb, Director of the Tel Aviv Museum, curated a wonderful exhibition and catalogue of Bergner’s works in 1957.

Caustic Cover Critic blog amazingly found some book covers designed by Bergner.

.jpeg)

.jpg)